Foundation of Museum of Modern Art (FoMMA)

FoMMA Trust is a non-profit educational and cultural entity with the aim of promoting the study and intelligent appreciation of art and architecture, in its contemporary manifestations as well as in a wider historical context. FOMMA’s objectives include the setting up of museums of modern and contemporary art, as well as art libraries in Pakistan. The FOMMA DHA Art Centre is a refurbished 19th century army barrack located in the beautifully landscaped Zamzama Park. The Centre has, over the years, held book launches, exhibits, screenings and collaborative events including ‘Art in the Park’ (art classes for children) and discursive talks by preeminent artists and curators. Its mission statement reads: “To create and run a centre of excellence, committed to the promotion, dissemination and documentation of arts and culture in order to confer a visible cultural dimension to society.”

Participating Artists:

Shalalae Jamil

Born in 1978 in Karachi (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Karachi (Pakistan)

Shalalae Jamil was born and raised in Pakistan and educated at Bennington College, USA and at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, USA. She has exhibited work in Pakistan and India, the US and the UK. She has been on the faculty of Beaconhouse National University, Lahore; National College of Arts, Lahore; and the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Karachi, where she was head of the Postgraduate Diploma Course In Photography. Her work is in several private collections, including the Arts Council in Pakistan and the Devi Art Foundation in India. Using photography, film, video, installation and elements of performance, she continually investigates how perception and meaning are altered by the shifting parameters of private and public space. Sometimes poetic, but often straightforward, her work uses the generic to address unspoken aspects of shared experience.

Of her work for KB17, Shalalae Jamil writes: “The name Kodak and its visual branding have been, for the major part of the last century, synonymous with the rise and dominance of photography as a popular art form. This body of work brings attention to the brand’s signage as it appears currently in Karachi: beleaguered, fading and becoming increasingly irrelevant. Witness to an era, to the processes of change and disintegration, to the inevitable clash between old and new; the at once beautiful and distressed symbol is emblematic in the most profound way, carrying with it the past, present and future of photographic practice. It is this history and ‘now-ness’ that I grapple with, through a series of photographs that are simultaneously a tribute and a space for reflection.”

The Lock from The Kodak Project, 2017.

Photograph

187 x 140 cm.

Courtesy the artist

Hamra Abbas

Born in 1976 in Kuwait City (Kuwait)

Lives and works between Lahore (Pakistan) and Boston (USA)

Hamra Abbas received her BFA and MA in Visual Arts from the National College of Arts, Lahore in 1999 and 2002, respectively, before going on to the Universitaet der Kuenste in Berlin where she did the Meisterschueler in 2004. Her works are part of notable international public collections including the Burger Collection, Hong Kong; Vanhaerents Art Collection, Brussels, Belgium; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas, USA; Kadist Collection, Paris, France; British Museum, London, UK; Devi Art Foundation, Gurgaon, India; Kiran Nader Museum of Art, New Delhi, India; Art In Embassies Collection, USA; Koç Foundation, Istanbul, Turkey and Borusan Contemporary Art Collection, Istanbul, Turkey. She is the recipient of the Jury prize at Sharjah Biennial 9, the Abraaj Capital Art Prize in 2011 and was shortlisted for the Jameel Prize in 2009.

Hamra Abbas has two works on view at KB17. In One Rug, Any Colour, she uses a selection of coloured nylon prayer rugs bought by her on Amazon. According to the artist, prayer rugs depicting the Kaaba have recently fallen out of favour, unlike in the past, when such images on prayers rugs were quite common. The artist found it nearly impossible to find one in the markets of Lahore today. The piece recalls an incident on Umrah, when a woman handed the artist one in a small bag as she was leaving the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina. Her own personal Barakah gift, this work also continues the artist’s fascination with colour and of representations of the Kaaba, recalling her 2013 series ‘Kaaba Picture as a Misprint’. The other work, Bodies, was carved from sheesham and then painted by the artist. This hyperrealist sculpture creates icons out of the ordinary and is a testament to the artist’s observance of everyday life in the homes and on the streets of Lahore. Bodies is a group of intricately carved wooden footwear taken from photos Abbas had taken outside the entrances to holy sites and family homes – a marker of segregation between inside and outside, clean and dirty, sacred and the profane. Each of these sculptures has been timelessly rendered, giving the original mundane objects a weight and presence that goes far beyond the accidental.

Bodies, 2016.

Sheesham wood, oil paints

35.6 x 15.2 cm (each)

Courtesy the artist and Lawrie Shabibi, Dubai

Sadia Salim

Born in 1973 in Hyderabad (Pakistan)

Lives and work in Karachi (Pakistan)

Sadia Salim graduated with a B.Des from the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture (IVS), Karachi, and completed her Ed.M. in Art and Art Education at Columbia University, New York. She is a practicing artist and recipient of the Commonwealth Arts and Crafts Award and Fulbright Scholarship. She has been part of conferences, residencies and exhibitions in Pakistan as well as internationally. Salim has extensive experience in teaching art and design at the undergraduate level including coordinating the Department of Ceramics at IVS (2005 - 2010). Currently she is Associate Professor and teaches in the Department of Fine Art; she also writes essays on art and craft in newspapers, catalogues and journals.

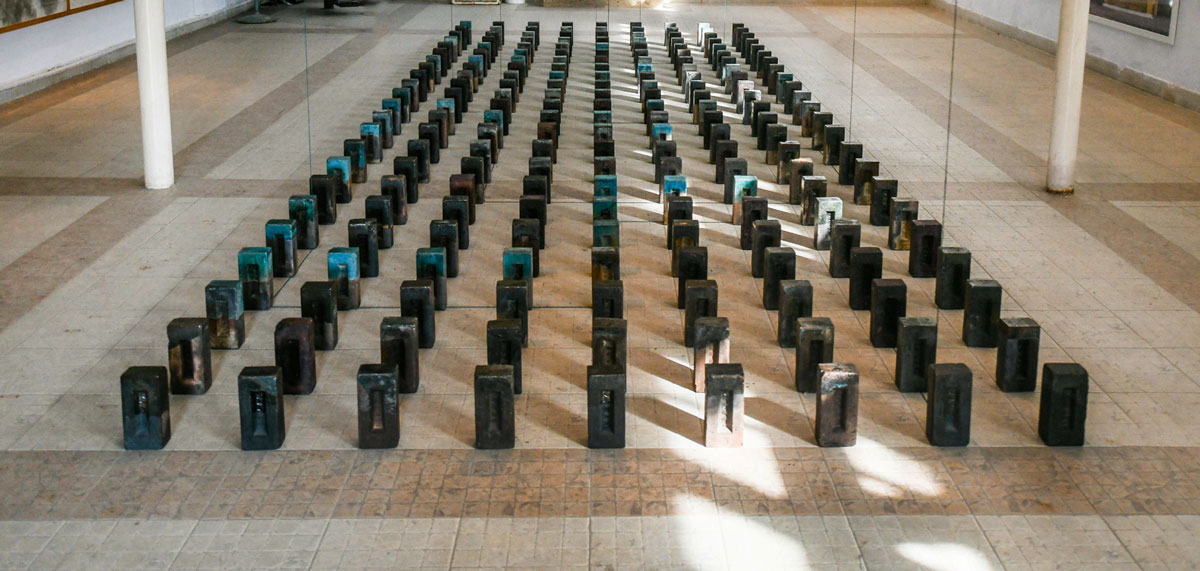

Of her work for KB17, Sadia Salim states: “A brick – a found object, ubiquitous and functional, centuries old or new, quiet and observant, made by hands of an unknown person and stamped with a factory’s logo. Within its mass, and as Antony Hudek asserts, ‘is a trove of disguises, concealments, subterfuges, provocations and triggers that no singular, embodied and knowledgeable subject can exhaust.’[1] Therefore the site specific brick installation proposes nothing to the viewers through the words of the artist, enabling them to witness, sense, interpret, and make meaning of the visual. However, as these reticent objects stare back at us, they witness us and our lives, and those who came before us or will come after. What is it that we want these objects to see and interpret?”

[1] Detours of Objects – Antony Hudeck

Untitled, 2017.

Clay brick, glazed and Raku fired

Dimensions variable

Courtesy the artist

Adeela Suleman

Born in 1970 in Karachi (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Karachi (Pakistan)

Adeela Suleman received her BFA from the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Karachi in 1999 and before that did her MA in International Relations from Karachi University in 1995. Currently Suleman is Associate Professor and Head of the Fine Art Department at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Karachi and is Coordinator of Vasl Artists’ Association, Karachi. Suleman has exhibited in numerous solo exhibitions, most recently at Gandhara Art Gallery, Karachi (2017); Aicon Gallery, New York, USA (2017); Davide Gallo Gallery, Milan, Italy (2017); Canvas Gallery, Karachi (2015); Aicon Gallery, New York, USA (2014); Canvas Gallery, Karachi; (2012); Alberto Peola Gallery, Turin, Italy (2012); Aicon Gallery, London, UK (2011); and Rohtas Gallery, Lahore (2008). She has also taken part in group exhibitions at notable Museums and foundations including, Pinakothek Der Morderne, Munich, Germany; Gaasbeek Castle Museum, Brussels, Belgium; A4 Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, Australia; Singapore Art Museum; National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taichung, Taiwan; Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, USA; Devi Art Foundation, Gurgaon, India; and the Asia Society, New York, USA, among others. Her works are part of notable international public collections.

Adeela Suleman sees her works as biographical, in the sense that what she makes tells us something about who she is and where she comes from. She is deeply rooted in tradition, culture and religion, yet she is also acutely aware of the urban and political realities that surround her in modern day Karachi. In her work the formal and sociological aspects of these two parallel worlds come together as a poetic document to her life. Adeela Suleman draws attention to troubled sectarian and gang-led violence in Pakistan. Drawing from the tradition of Islamic art, Suleman moulds hardened steel and co-opts found objects to memorialize the countless killings within her country. Of her work on view at KB17, Suleman writes: “The continuous and escalating cycle of violence and unrest plaguing Pakistan is not only leaving its mark on the awareness and memories of individuals, but has begun seeping into every space and landscape of its citizens’ daily experiences and collective consciousness.”

Falling Down, 2012.

Stretcher, stainless steel, powder paint

185 x 350 x 13 cm.

Courtesy the artist

Anwar Saeed

Born in 1955 in Lahore (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Lahore (Pakistan)

Anwar Saeed graduated with a BFA from the National College of Arts, Lahore in 1978 and completed his postgraduate studies at the Royal College of Arts in London. He has exhibited widely in Pakistan and has participated in group shows in the US, Australia, Norway, Egypt, Jordan and India. He has been Associate Professor at the National College of Arts, Lahore since 1986.

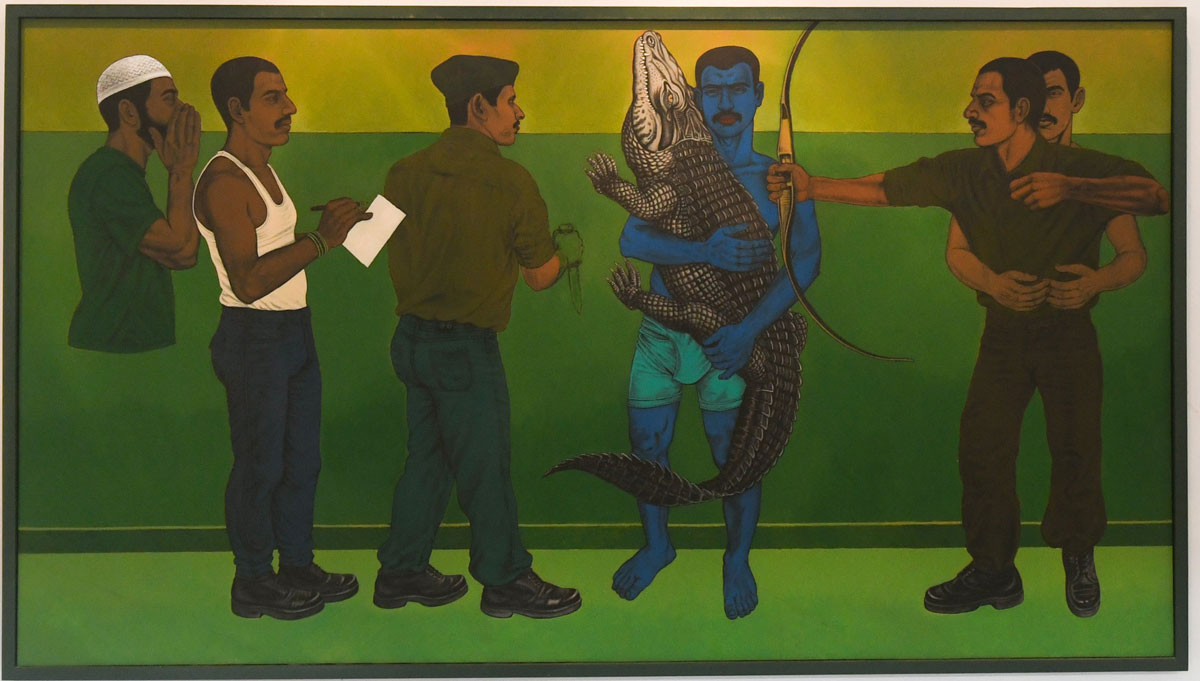

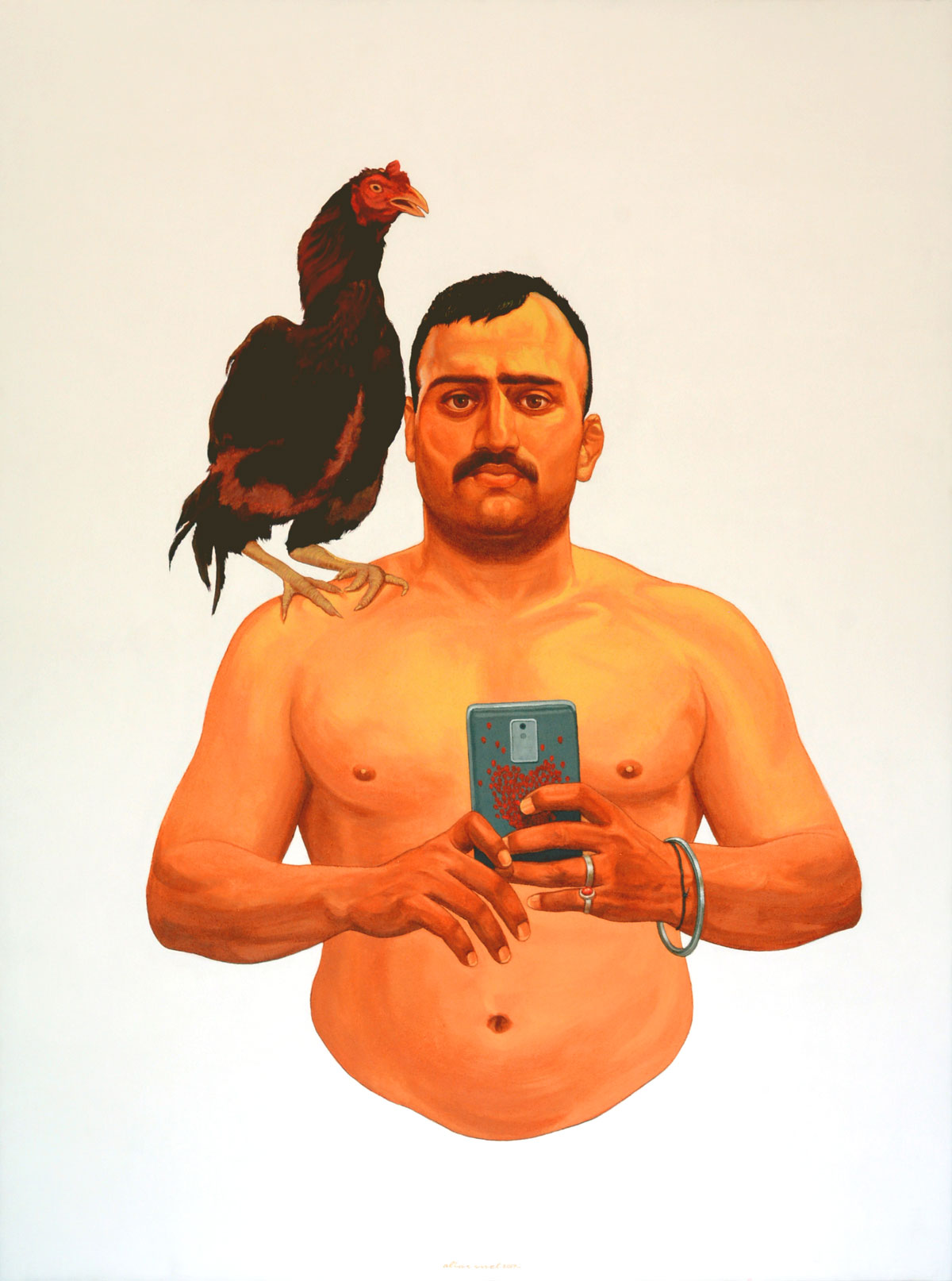

Anwar Saeed has submitted a painting for KB17. He writes of his wider practice: “Parallel to all kinds of changes in medium, technique, materials and more, what I can see as almost constant in my work, over the years, is the presence of figure--the physicality of it. The pleasure of drawing and painting the body is the thing that keeps me coming back to my work. It also appears as a site where you can locate discussions of marginality, dispossession, love, betrayal, sin, violence, death and rebirth.”

A Casual State of Being in a Soul Hunting Haven, 2017.

Acrylic on canvas

152 x 274 cm.

Courtesy the artist

Gordon Cheung

Born in 1975 in London (UK)

Lives and works in London (UK)

Gordon Cheung studied painting at Central St Martins College of Art and at the Royal College of Art, London from where he graduated in 2001. He is best known for his epic, hallucinogenic landscapes constructed using an array of media including stock page listings spray paint, acrylic and, most recently, inkjet and woodblock printing. Gordon Cheung’s work is in international collections including MoMa, Hirshhorn Museum, Whitworth Museum, ASU Art Museum, The New Art Gallery Walsall, Knoxville Art Museum, Hiscox Collection, Progressive Arts Collection, UBS Collection and the Gottesman Collection. Notable group exhibitions include the John Moores Painting Prize 24, The British Art Show 6 and the Azerbajjan Pavillion at the 56th Venice Biennale.

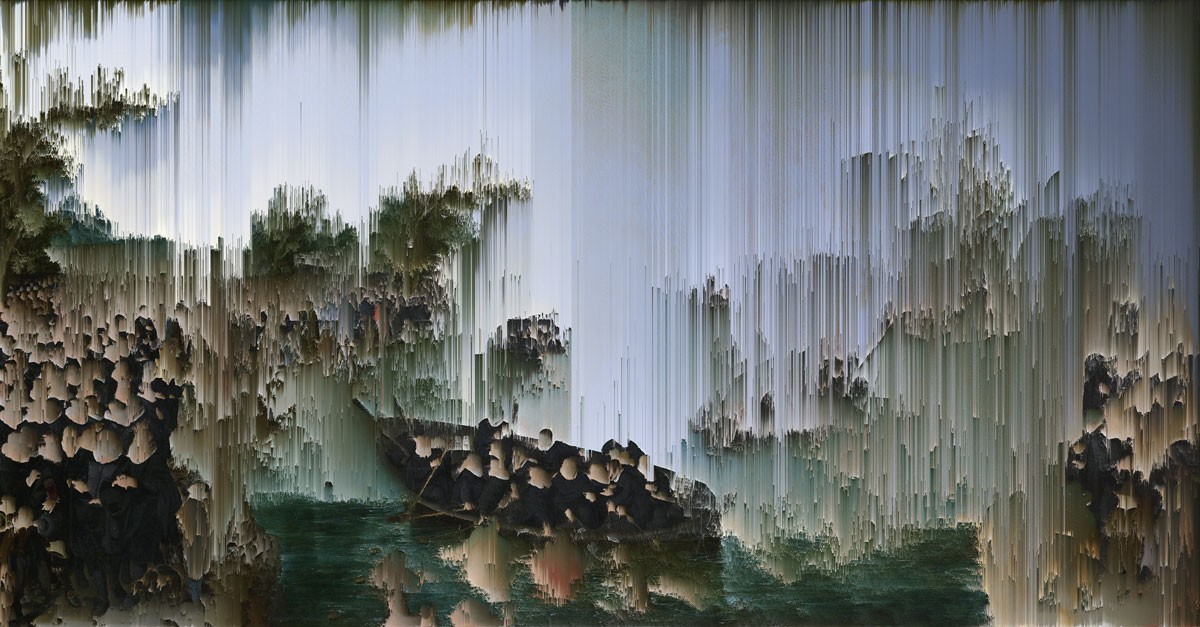

Fishing for Souls is originally a 1614 oil on panel painting by the Dutch Golden Age artist Adriaen van de Venne in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. It was made during what is considered to be the birth of Modern Capitalism with the rise of the East India Trade Company built from militarised trade routes, colonisation and slavery. At the left are the Protestant and at the right the Catholic. Both fish for souls in the wide river dividing them showing an allegory of partition between the Northern and the Southern Netherlands that occurred with the Beeldenstorm, a destructive period of religious imagery. The high resolution photograph of the painting has had an open source sorting algorithm re-organise its pixels into over 4000 images where nothing is erased, destroyed or copied. These are then stitched and looped together in an animation programme. The visual results are a form of deliberate glitching. A glitch is usually a mistake in a technological representation of an image but here it is appreciated for its beauty and how it reveals the multiple dimensions of representation. The digital fracturing of the image simultaneously reveals the technological space of what creates the image, the physicality of the screen and the illusion of image. In these multi-dimensions of reality we are offered a space to meditate and question the narratives of histories. By using this computational code to re-order the pixels the effect results in a mesmerising digital sands of time effect that metaphorically suggests the repetition of histories from the classical to the digital age.

Still from Fishing for Souls (After Adriaen Pietersz. van de Venne, 1614), 2015.

6 min. film loop with 3 hour soundtrack loop

Courtesy Edel Assanti and Alan Cristea Gallery, London

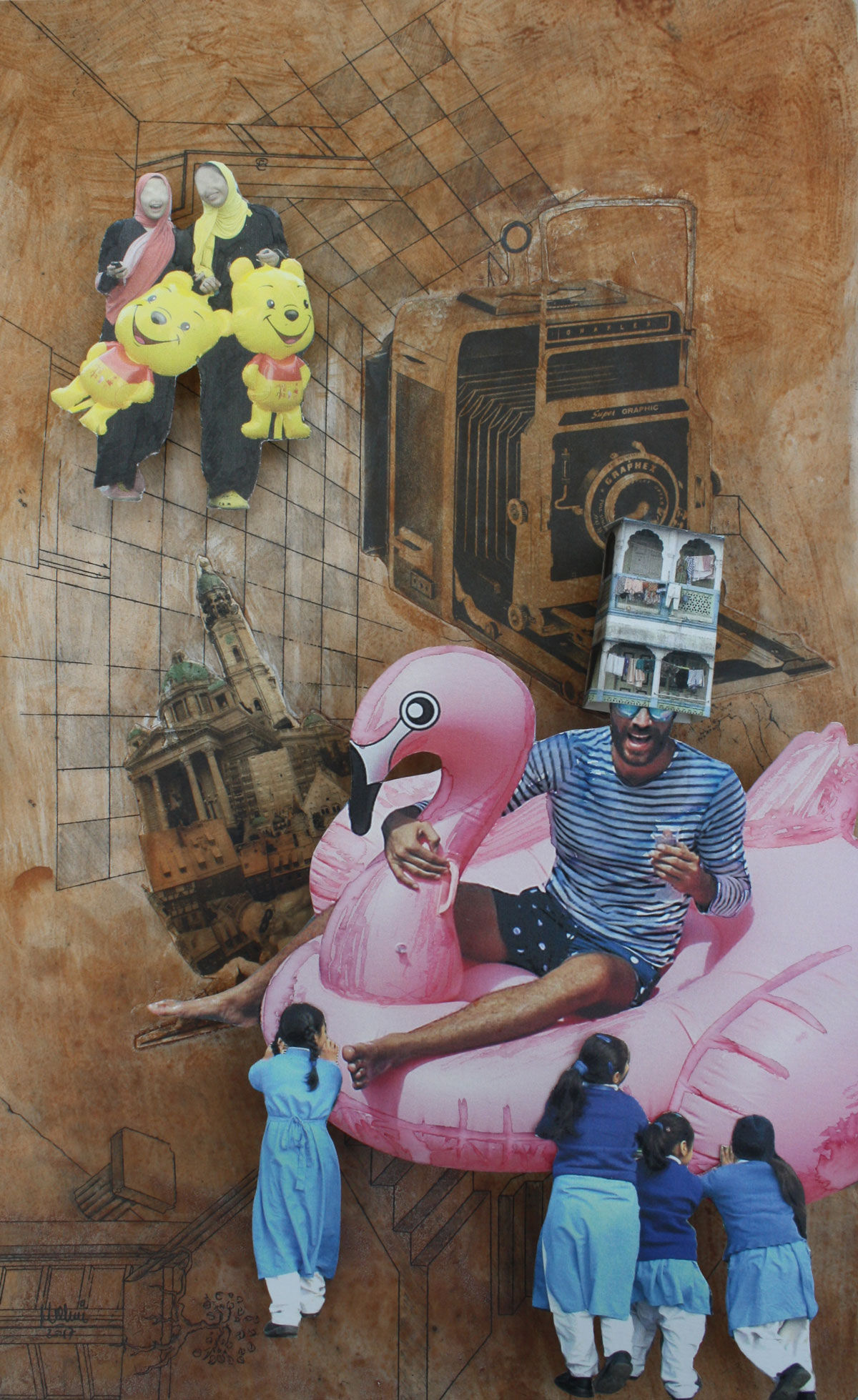

Samra Roohi

Born in 1990 in Karachi (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Karachi (Pakistan)

Samra Roohi received her BFA (Honors) from Karachi University, Department of Visual Studies in 2012. She has participated in numerous group shows, including “Awaaz: Baldia Factory Inferno,” Karachi Arts Council; “All Puns End with Guns,” Rohtas Gallery, Islamabad; “Pursukoon Karachi,” Karachi Arts Council; “FRESH!” Amin Gulgee Gallery, Karachi; “Dil Phaink Alchemy,” South Bank Centre London, UK; “Unwritten Thoughts,” IVS Gallery, Karachi; “The 70's: Pakistan’s Radioactive Decade,” Amin Gulgee Gallery, Karachi; “We the People,” Sadeqauin Gallery, Frere Hall, Karachi; and “Ibtidah,” Studio Seven Gallery, Karachi. She is the recipient of the Art Commendation Award by Ladiesfund and a scholarship by VM Art Gallery.

Samra Roohi writes of her lenticular print on view at KB17: “My work talks about changing perceptions. I use others’ ways of presenting reality and manipulate it according to how I perceive it. My work debates the actual projection of what is happening in our society, but it only provides you with a picture. How you perceive it depends upon who you are.”

Untitled, 2012.

Lenticular print

122 x 92 cm.

Courtesy the artist

Mohsin Shafi

Born in 1982 in Sahiwal (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Lahore (Pakistan)

Mohsin Shafi received both his Master’s and BFA degrees from the National College of Arts (NCA), Lahore. He is currently a visiting faculty member in the MA Visual Arts Department at the NCA, Lahore. Shafi has showcased his work at prominent galleries in Pakistan as well as in international exhibitions. He was part of the Vasl Artists residency in 2010 in Karachi and was an Artist in Residence at the Rondo Studios in Graz, Austria in 2012. As well as being included in significant collections in Pakistan, his work is in the permanent collection of The Museum of Sacred Art (MOSA) in Belgium and recently been acquired for the permanent collection of the Department of Book Art at Mills College, San Francisco. His images have also been used as covers for books by Agnar Artúvertin, Martin Walser and Gabriel Rosenstock, as well as other writers and poets. Mohsin is an active member of the Awami Art Collective, which is a unique group of artists and activists intervening in the public space in Pakistan for the cause of peaceful coexistence and the celebration of diversity.

Mohsin Shafi writes of his submission for KB17: “The visuals in the installation intend to articulate the notions of safety within physical and intellectual spaces of representation: the safety of being visible for having non-conforming ideas within a militant-state and of being proclaimed the Other by the spectator’s eye. This is the danger of being seen through the lens of sexual taboos, gender binaries, ethnic hierarchies, religious freedoms and the public availability of that information. These are the struggles of being looked at and judged, of being reduced to a cliché or a cultural smear. Questioning how to bear witness to the complexities of the present times, the installation responds to the aesthetic and ambiguities of our society.”

This is Not the Way Home, 2017.

Mixed media installation

305 x 549 cm.

Courtesy the artist

Sungjin Song

Born in 1974 in Busan (South Korea)

Lives and works in Busan (South Korea)

Sungjin Song explores the habitat and lifestyles of urban dwellers through photography, installation, video and interactive art. Through his work, he chronicles urban change and how the structuring and restructuring of cities impact their citizens. Song completed a PhD course at Busan National University. Since then, he has had 11 solo shows and participated in numerous group shows, both in Korea and abroad. He has also coordinated public art projects in different countries, including projects at the Museum of Kaohsiung/Taiwan, ARKO Museum, Gwangju Museum of Art and the Busan Museum of Art.

Recently, in Berlin, Song initiated a project called “Postures,” which investigates the posture/posturing of people in the private and public space. He will bring this project to Karachi and some of the work he documents there will become part of the Biennale. Of his work on view at KB17, Song states: “Suppose a virtual city has things in common with a real one, then make people who live in an actual city play a game which is very simple and physical, like hanging onto a horizontal bar or standing on a balancing beam all together at the same time. I then capture their collective postures in photographs and on video. The aggregate of images confronts the viewer with people from different backgrounds all engaged in a single activity. The question is: will the viewer be able to identify who is who? The exercise is intended to make us think of our perpetual efforts to move forward and keep our balance; of why we keep on doing this; and of what we feel about the present.”

Postures-Hang on, Balance, 2017.

Digital print, photo installation

90 x 250 cm.

Ali Azmat

Born in 1973 in Multan (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Lahore (Pakistan)

Ali Azmat received his BFA from the University of the Punjab, Lahore, in 1997. He then went on to complete his MFA (in painting), in 1999, and his M. Phil in Fine Arts (studio practice), in 2015, from the same institution. His work has been shown in numerous group exhibitions, and he has mounted several solo exhibitions, both nationally and internationally. Azmat received the National Excellence Award from the Pakistan National Council of Arts in 2003. His artistic practice embraces the aesthetics of both the figurative and landscape painterly traditions of the Punjab. He frames this traditional sensibility within a truly contemporary and relevant oeuvre of subjects, exposing existent social hierarchism and exploring the concepts of the ‘local’ in a nuanced manner that subverts current artistic trends in peripheral visual culture toward pandering to notions of neo-exoticism.

Dangal, Azmat’s painting for the Karachi Biennale 2017, derives its subject matter from his father’s obsession with Akhara culture throughout the artist’s formative years. Azmat explains: “The influences, inspirations and even the morals of the Akhara culture were in practice in our home. In this context, the psychological patterns of my youth developed into series of symbols and metaphors that I have subjectively interpreted and furnished in my artwork.” The work is fecund with dichotomy and contrast, representing the inherent contradictions in societal stratification. Azmat’s depiction of a strident, muscular and rigid figure is a visual embodiment of masculinity, and the Dangal’s placement in an antithetically contemplative and emollient setting highlights the inherent chauvinism of such a sub-culture. The painting, however, transcends such a specific critique, metonymously manifesting the hypocrisy and multitudinous contradictions imbued within any form of structuralised misogyny.

Dangal, 2017.

Acrylics on canvas

122 x 91 cm.

Courtesy the artist

Aakif Suri

Born in 1982 in Dera Ghazi Khan (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Lahore (Pakistan)

In 2006 Aakif Suri procured a BFA in Miniature Painting from the National College of Arts, Lahore. He now works as an Assistant Professor at both his alma mater and the Pakistan Institute of Fashion and Design (PIFD), Lahore. His work has been shown both locally and internationally at a variety of group exhibitions, solo shows and art fairs, the latter including the Basel Art Fair, the Melbourne Art Fair and Slick Art Fair, Paris. Suri’s technical practice has very much been shaped by his training in miniature painting, the practice and popularity of which, since its reintroduction as a major subject to the NCA’s Fine Art curriculum in 1982, has experienced a dramatic resurgence. His art practice is informed by his rural upbringing in the generally underprivileged Dera Ghazi Khan district of the Punjab. This manifests itself in his work by reflecting and promulgating the issues, concerns and cultural sensibilities of his community, which often remain unvoiced due to its socio-political and demographical context.

SANAM is a work in which Suri expands on his sensitivity for naturalistic detail, acquired in his training as a miniaturist, on a larger scale. The work simultaneously plays with notions of ethnicity, technical tradition and the apportion of cultural significance. Whilst Suri’s work is somewhat of a departure from the technical tradition of contemporary miniature painting, the post-colonial derivative of the Mughal painterly tradition of musawwari, its influence is still conspicuous, even though the scale of the work is far from miniature. As Murad Khan Mumtaz writes: “In a global art economy, miniaturists are now encouraged to invoke ‘ethnic’ aesthetics; however, paradoxically, they continue to be influenced by and judged according to an established European canon.”[1] In this context, Suri’s departure in scale and subject matter clearly subverts this pressure to conform to the whims of the global art market. However, his subject matter, a modestly garlanded cow, directly refers to his ethnic background in which cows are of vital cultural significance due to the region’s cattle industry. The title of the work, SANAM, a name meaning ‘beloved’ in Arabic, further emphasises the symbolic importance of the cow depicted. In his work, Suri not only undermines the external categorisation of the technical tradition of miniature painting, he creates a visual metaphor for his ethno-cultural context within his highly-skilled aesthetic framework.

[1] https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/map/miniature-painting-in-pakistan-divergences-between-traditional-and-contemporary-practice

SANAM, 2017.

Graphite and powder pigment on archival paper

116 x 198 cm.

Courtesy the artist

Broersen & Lukács

Live and work between Berlin (Germany) and Amsterdam (The Netherlands)

Margit Lukács (b, 1973, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) & Persijn Broersen (b. 1974, Delft, The Netherlands) are artists living and working between Amsterdam and Berlin. They work in a wide variety of media—most notably video, animation and graphics—producing a myriad of works that reflect on the ornamental characteristics of today's society. With video pieces that incorporate (filmed) footage, digital animation and images appropriated from the media, they demonstrate how reality, media and fiction are strongly intertwined in contemporary society. Broersen and Lukács studied at the Sandberg Institute and at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. Their films, installations and graphic work have been shown internationally, at a.o. Biennale of Sydney (Australia), Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (the Netherlands), MUHKA (Belgium), Centre Pompidou (France), Shanghai World Expo (China), and Casa Enscendida (Spain).

Broersen & Lukács have two videos on view at KB17. In Establishing Eden, the artists focus on the establishment shot: the moment a landscape is identified and becomes one of the main protagonists in a film. In blockbusters like Avatar (James Cameron, 2009) and the film series Lord of the Rings (Peter Jackson, 2001-2014) these shots have been used to capture and confiscate the nature of New Zealand, propagating itself as a new Eden, ever-green and unspoilt. Here fiction takes over reality: mountains and forests exist under the name of their cinematic alter-egos. Broersen & Lukács traveled through the wilderness of New Zealand to capture these landscapes and with that, they appropriate the nature of New Zealand once again. Creating an architecture of fragments connected by the camera-movement of a perpetual establishment shot, they show this Eden as a series of many possible realities, an illusion that just as easily comes together as it falls apart. In the second video, Stranded Present, the vertigo effect of time in today’s culture makes the present appear as if woven out of many pasts. Transformed, shifted or mutilated, historical motifs have found their home in the adornments of many past and future households. While searching for the strength and sustainability of certain patterns, Broersen & Lukács stumbled upon the 19th century illustrations of the ruins of Palmyra in the Parisian Bibliothèque Fornay, a library of decorative arts. They reconstructed this once flattened motif of a temple, depicting its endless dimensions—plastic, malleable and untouchable—as a liquid body, transforming over time. On the night of its first appearance in public, ISIS took control of the historic city of Palmyra and, with that, expropriated the meaning of Broersen & Lukács’ work. And, nevertheless, or perhaps precisely because of this, the motif is again nestled in our brains, as a stream that, once settled in its bed, will flow on for ages.

Still from Stranded Present, 2015.

Video installation, 18 min. (loop)

Courtesy the artists