Alliance française Gallery

The Alliance française Gallery is designed to support artists in the city, and increase intercultural exchange. A site of interdisciplinary discourse, the gallery exhibits both the work of artists invited to Karachi by AfK and that of local artists, as well as presentations, lectures, workshops and performances.

Participating Artists:

Guillaume Robert

Born in 1975 in Nantes (France)

Lives and works in Hotonnes (France)

Over the past fifteen years, Guillaume Robert has developed videographic, sculptural and photographic projects and has taken part in collaborative processes and research residencies. He is involved in the Bermuda project, which aims to build a collective art production center in Le Grand Genève. He has had numerous solo and group shows at various art centers and galleries throughout Europe. In 2016, his first monographic publication, Parages, was published by Edition Analogue and Galerie Françoise Besson (Lyon, France). His works are in various private and public collections, including the Fonds National d'Art Contemporain (France).

For KB17, Guillaume Robert has created a site-specific installation, UP TO THE BIG EYE, at the Alliance française de Karachi, from which he has also created a four-minute video work using drone footage with a bird’s eye perspective of the installation. He has also submitted a video called Drina as well as a series of drawings. Of his video and drawings, Robert writes: “Drina shows the reenactment of the building of a mini-hydroelectric station in Goražde (Bosnia). During the siege of the city that took place between 1992 and 1995, these improvised machines were attempts to open up the area — to be able to listen to the radio and gain access to the outside, to have a source of light and to be able to use medical equipment. A similar machine was re-made in Juso Velic's garage in June 2011. The micro-station was set afloat on the river, attached to the main bridge of the city over the Drina. Through this very concrete focal point (the reproduction of a micro-hydroelectric station), the process became one of relaying and documenting a heroic experience: the Goražde inhabitants' resistance to the siege that took place fifteen years before. I will also present ten drawings entitled Points of View. Each of them shows an Algerian watchtower. During and after the Algerian civil war, the military, public services and private companies built many of these lookout points around their infrastructures. I have discreetly photographed some of them and then drawn them as architectural projects or technical drawings.”

Still from Drina, 2012.

HD video, stereo, 22:30 min.

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Françoise Besson, Lyon

Moeen Faruqi

Born in 1958 in Karachi (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Karachi (Pakistan)

Moeen Faruqi is an artist and poet whose work aims to capture the everyday alienation of modernity. His paintings have been exhibited widely within Pakistan and internationally in Canada, Italy, Singapore, Bangladesh, the United Kingdom and India. His most recent solo exhibitions were at Canvas Gallery, Karachi, and at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture Gallery, Karachi. His poems have been published in various literary journals in Pakistan and abroad. His art practice is, at its basis, an existential investigation into the contemporary human experience of urbanity; his premise being that the relentless force of globalisation and international uniformity only lead to a greater sense of estrangement and separation. Primarily narrative in nature, his work finds its voice in figures who confront the viewer, almost as if they are pleading for relief from distorted relationships and artificial interactions. As such, the actors in his bizzarist theatre attempt to elicit a response of self-recognition from the audience. His technical practice reveals a profound fascination, almost a primitive enjoyment, in the creative process of painting a surface, manipulating and cajoling the flow of paint on a plane to explore new directions and avenues in his artwork.

Faruqi’s diptych for the Karachi Biennale 2017, Clifton Bridge, represents a stylistic transition from his narrative-based work to a concern with forms. It experiments with abstraction, with his figures becoming part of schematic colour fields, dispossessing them of their individuality, symbolising the destruction of selfhood in the contemporary metropolis. Commenting on the new artistic direction displayed in his work, Faruqi states: “It is almost as if the figures have become part of the background, or a part of the larger scheme of fragmented blocks of color. The idea is to fabricate and present a new imagery, but also to reduce characters in the painting to mere forms, not personalities.” Whilst aesthetically a move away from his previous work, Clifton Bridge conforms to the general theme of urban existentialism in his art practice, highlighting Faruqi’s perpetual experimentation with the medium of painting as a means to explore this thematic.

Clifton Bridge Is Falling Down, 2017.

Acrylic on canvas

152 x 305 cm.

Courtesy the artist

Farida Batool

Born in 1970 in Lahore (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Lahore (Pakistan)

Lahore based visual artist and researcher in visual culture, Farida Batool completed her Doctorate in Media and Film in 2015 from SOAS, London University. In 2003, she acquired her Master of Arts in Art History and Theory (Research) from the College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Australia, and received her Bachelor of Fine Arts from National College of Arts, Lahore, Pakistan in 1993. Batool has taught in many universities, including University of New South Wales, Australia, Beaconhouse National University, and National College of Arts, Lahore, where she is currently officiating the Department of Communication and Cultural Studies. She has travelled extensively and presented papers and presentations at international conferences and workshops including Yale University, USA; Society for Cinema and Media Studies, Montreal, Canada; Oxford University, UK; Jawaharlal Nehru University, India; Itau Cultural, Sao Paulo, Brazil; UNESCAP Jordan; UNIFEM Bangladesh; and has published papers and articles including authoring a book on figurative representation in Pakistani popular culture titled Figure: the Popular and Political in Pakistan, 2004. Batool is interested in developing a comprehensive cultural critique of Pakistani, Islamic, and Western modes of everyday life, which is also reflected in her recent short film for the BBC online called The Clash of Masculinities. Solo exhibitions include “By the High Walls and Closed Gates,” Gandhara Art-Space, Karachi (2016); “Kahani eik shehr ki,” Rohtas 2, Lahore (2012); “Love in the Time of Cholera,” Canvas Gallery, Karachi (2009); “Maa Tujhe Salaam,” Aicon Gallery, New York, (2009); “Lahore My Love,” Rohtas 2, Lahore (2008), “The Blink,” Rohtas 2, Lahore (2006). Selected group shows include “Where Three Dreams Cross: 150 Years of Photography,” Whitechapel Gallery, London (2010); “Forces,” Portimao Museum, Algrave, Portugal (2009); “Tradition,Technique,Technology II,” Aicon Gallery, Palo Alto, USA (2008); “Beyond Borders: Art from Pakistan,” National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai, India (2004); “Interstation: Artists Beyond Boundaries,” Kudos Gallery, Sydney, Australia (2003); and Cairo Biennale, Egypt (1995).

Farida Batool has two works on view at KB17. She uses lenticular prints in which the image changes when the viewer moves position, in order to portray contrasting realities. The two images are often related through the notion of memory or history, with the “earlier” image being both partially erased but also constitutive of the “later” image. This medium facilitates in addressing the social and political realities of Pakistan with a nuanced and poetic expressions often rooted in and supplemented by personal experience.

Dekhna manaa hai, 2009.

Lenticular prints

Dimensions variable

Courtesy the artist

(Detail)

Affan Baghpati/Syed Arsal Hasan

Affan Baghpati (b. 1991, Karachi) obtained his BFA from the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Karachi, and completed his Master’s in Art and Design Studies at SVAD, Beaconhouse National University, Lahore. Baghpati’s art practice is concerned with re-contextualising discarded domestic objects into the artistic sphere, identifying their notional value through their design, aesthetic, form and functionality. Syed Arsal Hasan (b. 1989, Karachi) is a theatre director, actor and playwright, as well as one of the founding members of the Mandarjazail Collective. He graduated from the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture with a Bachelor’s degree in Communication Design. Arsal’s artistic practice draws its inspiration from the writings of Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Mirza Ghalib as a way of examining South Asian culture from a structuralist perspective. His work is deliberately designed so that it transitions with fluidity between film, theatre and art with a malleable visual vocabulary.

Their collaborative sculptural installation for the Karachi Biennale 2017, Aasaih-e-Manzil, is an artistic response to Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s poem, ‘Do Ishq’ (Two Loves). Using abandoned objects to symbolise the personified ‘motherland’ that Faiz yearns for in his verse, the duo visually transpose the notion of cultural vulnerability and loss latent in the poem. The arrangement and composition of the objects aesthetically recalls the structure of poetic verse, and the selection of the objects themselves imbues the structure with a contemplative, nostalgic tone that somehow atmospherically transports the viewer to a forgotten past.

Aasaih-e-Manzil, 2017.

Found objects, furniture.

Dimensions variable

Shahzia Sikander

Born in 1969 in Lahore (Pakistan)

Lives and works between New York (USA) and Seville (Spain)

Shahzia Sikander received her BFA in 1991 from the National College of Arts, Lahore, in miniature painting. Sikander received her MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1995, and from 1995-1997, she participated in the CORE Program of the Glassell School of Art at The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Sikander has been the subject of major international exhibitions around the world, including, amongst others, MAXXI | Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Rome (2016-17); Asia Society Hong Kong Center, Hong Kong (2016); the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao (2015); Bildmuseet Umea, Sweden (2014); Linda Pace Foundation, San Antonio, Texas (2012-13); IKON, Birmingham (2008); Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney (2007); Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (2007); The San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego (2004); the Whitney Museum of American Art, Philip Morris/Altria Branch (2000); Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (1999); Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago (1998); The Drawing Center (1997); The Whitney Biennale (1997); and has participated in more than 400 group shows and international art forums. Sikander has received numerous grants, fellowships and awards.

Disruption as Rapture (2016) is a 4K single-channel video animation with original music by the Pulitzer-Prize winning composer Du Yun featuring musician Ali Sethi. The work is born from selected folios of the 18th-century Gulshan-i-Ishq manuscript and is permanently installed in the South Asian Galleries of the Philadelphia Art Museum. In 2015 the museum reached out to the artist to develop a multi-dimensional work to bring the historical manuscript in their permanent collection to life. The Gulshan-i-Ishq or the Garden of Love, an epic poem and an allegorical tale, was written in 1657–58 by Nusrati, court poet to Sultan Ali Adil Shah II of Bijapur. The poem is also written in Daccani Urdu and Persian Naskh script, the language of the Muslim elite in South- Central India, a North Indian Hindu love story recast as a Sufi tale for an Islamic court. The story is a classic tale of star-crossed lovers who must face daunting challenges and painful separation before they can unite. The poet recounts this tale of connection, separation, longing, and the final union of lovers by creating a world full of lush gardens and magical beings, where the love story emerges as a metaphor for a soul’s search for, and connection with, the divine. Disruption as Rapture calls into question the philosophical and the political, with the unfolding of narrative based on shifting migratory patterns, interactions, cultural quarantine, autonomous verbal and poetic languages, and the quest for the sacred in the personal.

Still from Disruption as Rapture, 2016.

HD video animation with 7.1 surround sound, 10:07 min.

Music by Du Yun featuring Ali Sethi

Commissioned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art for the Permanent South Asian Galleries

Unver Shafi Khan

Born in 1961 in Karachi (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Karachi (Pakistan)

Unver Shafi Khan set up his studio in Karachi in 1984 after returning from Kenyon College, USA with a BA in English Literature. His first solo show, in 1986, was at the Indus Gallery run by the iconic Ali Imam. This came about because of a meeting at the gallery with the late Dr Akbar Naqvi, F.N. Souza and Ali Imam. At that time, Unver met sporadically with Amin Gulgee, Durriya Kazi, Huma Bhaba, Naiza Khan, Elizabeth and Iftikhar Dadi, David Alesworth and Moeen Faruqi, as well as with Ardy Cowasjee, who opened the short-lived but influential Ziggurat Gallery in Karachi. It was in these early years that the artist also befriended the late Zahoor ul Alkhlaq, who stayed with him and worked in his studio towards his first show at Ziggurat. And the rest, Unver says, “is history.”

Unver Shafi Khan has created a giclee print on canvas based on a painting in acrylic for KB17. The image is of a large pink pig. Art critic Saquif Hanif has written of the artist and his oeuvre: “If the larger oil paintings are exercises in virtuosity and control and hinged mostly on solitary forms, the meticulously observed acrylic ‘miniatures’ collectively titled as the Fabulist series [as in taking inspiration from traditional fables] use a striking jewel-like visual narrative full of sexual wit and innuendo. This narrative content is drawn from a host of arts and crafts traditions and these paintings provide a sense of looking past the edge of the ordinary world into the domain of the phantasmagoric. Those made uncomfortable by the ostensible disjunction between Unver’s large work and these miniature scaled paintings need not be unduly alarmed as they share a common pictorial ethos. It is all there for the main part-the choice of the human figure as the basic unit of art, the saturation of colour, the mastery of rhythm, the sexuality, the relentless sense of fun- the only difference being one of scale and technique. The paintings in both mediums are profligate in their wholesale abandonment to feelings and flat-out appeal to the senses.”

HOLY SHIT!, 2017.

Giclee print on canvas and reworked again

183 x 137 cm.

Courtesy the artist

Rabbya Naseer

Born in 1984 in Rawalpindi (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Lahore (Pakistan)

Rabbya Naseer is a Lahore-based artist, curator, writer, critic and teacher. Her practice is broadly concerned with exploring the parallels between art and everyday life, highlighting their similarities in production, representation, reception, and interpretation. She views herself as a facilitator in the realm of cultural production, orchestrating situations of discourse and reciprocity through a variety of mediums and disciplines. With a keen interest in performative art, Naseer examines how encounters with the commonplace can spur the process of artistic creation. She obtained her Bachelor’s in Fine Arts from the National College of Arts, Lahore (2006), and was the recipient of a Fulbright scholarship for her Master’s in Art Theory and Criticism from SAIC, Chicago (2008-2010). She has participated in exhibitions, residencies and conferences in Pakistan, India, USA, UK, Dubai, China, Japan, Germany, Netherlands and Australia.

Naseer’s video work for the Karachi Biennale is part of her ongoing project that aims to develop an archive of Pakistani performance art. Her project investigates the many unique aspects and challenges imbued within the discipline of performative art; the ephemeral nature of a performance piece entails the necessity for photographic or video documentation, yet this residual evidence can never appropriately capture the experiential and sensory nature of the work for a member of the audience. Neither can this documentation fully describe the context of the performance, time and space being essential aspects in its realisation. However, without such recordings, and their compilation in an archive, the only remaining testimony of the work comes from the highly subjective perspective of the viewers, and the artist themselves, which must come in the form of mandatory ekphrasis. Naseer’s project examines the divergent, often oppositional aspects that constitute a performative piece of art. Naseer explains the thematic relevance of her project: “The Karachi Bienniale’s theme is closely aligned with the subject of my project. It’s a perfect setting to share a few works through a form that aims to explore the role of the ‘witness’ in relation to performance art.” Rabbya Naseer’s collaborative performance with Hurmat Ul Ain, Dropping Tears Together II, is also part of the Karachi biennale 2017.

Witness, 2017.

Video, 42:31 min.

Shakeel Siddiqui

Born in 1951 in Karachi (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Karachi (Pakistan)

Shakeel Siddiqui received his Diploma in Fine Art Painting from the Central Institute of Arts and Crafts, Karachi in 1975. He also studied at the Art Students’ League in New York from 1970 to 1972. At the the beginning of his career, he focused on figurative work and portraits in oil on canvas. Later, he moved on to still-life, also in oil on canvas. Since 1979, he has concentrated on super realism, also known as hyper realism. He taught at the Central Institute of Arts and Crafts, Karachi from 1986 to 1989 and at the Dubai International Art Centre from 1992 to 2004. He has had solo exhibitions of his work in Pakistan, the UAE, the UK, Canada and The Netherlands, and participated in numerous group exhibitions around the globe.

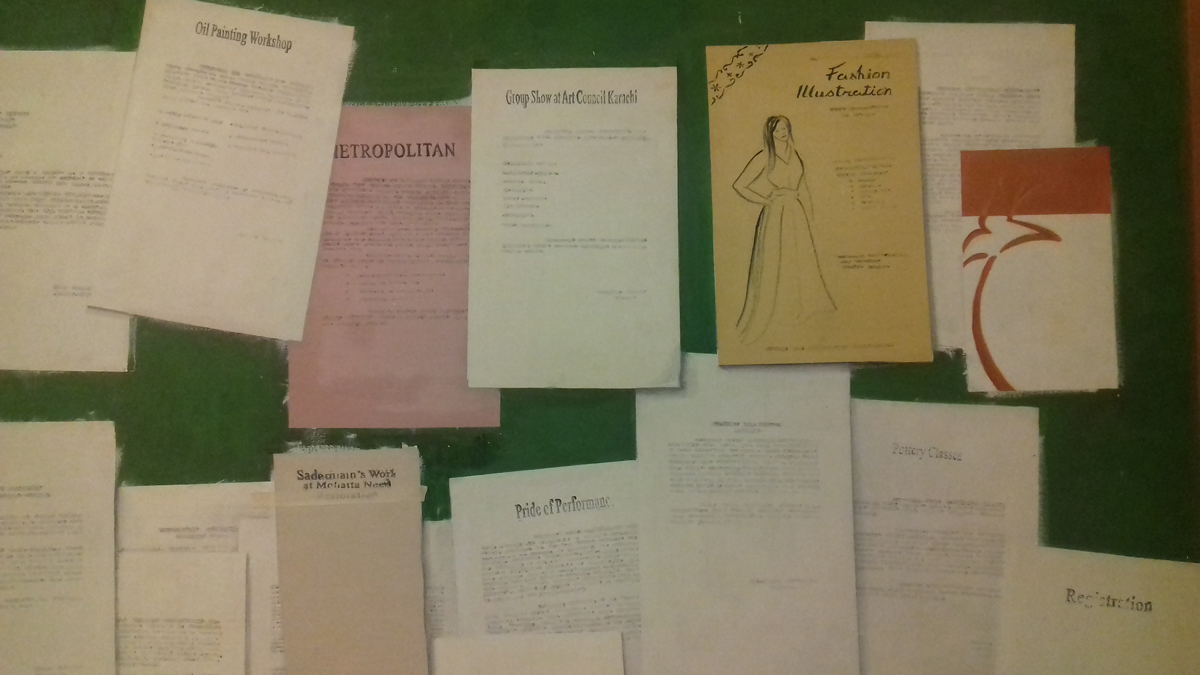

Of his work for KB17, Shakeel Siddiqui writes: “I am submitting one painting. The subject is a noticeboard. I have tried to capture the third effect of a noticeboard which everyone of us has experienced. I went through almost all the details including the lettering on the papers. Almost all the papers are white and overlapping each other (white on white) but they are still easily differentiated.”

Notice Board, 2017 (Detail)

Oil on canvas

91 x 91 cm.

Courtesy the artist

Sophia Balagamwala

Born in 1987 in Karachi (Pakistan)

Lives and works in Karachi (Pakistan)

Sophia Balagamwala is a Karachi-based artist, illustrator and curator. Her work draws from history, children’s books, political caricatures and animated films. She currently works at the Citizens Archive of Pakistan, and is the Lead Curator for National History Museum at the Greater Iqbal Park, Lahore. Her artistic practice explores the intersectional space in which history, fiction and nonsense converge. This derives from her interest in how stories are constructed, in particular, the myths of national heroes and national histories, and how these embody a subjective dialogue between so-called historical reality, apocrypha and mythification. These concerns find their way into Balagamwala’s practice through a visual language inspired by children’s books and political caricatures.

Hopes and Prospects epitomizes Balagamwala’s artistic practice, by presenting various caricatured candidates to the audience, each of whom is running to be elected as head of a fictional state. She presents each candidate in a gaudy television set, which seems to have come straight off the pages of an illustrated children’s book, creating a visual representation of each candidate’s ‘soap-box’. Balagamwala aptly describes the beauty and danger of caricature: “The humour of the caricature, in addition to acting as a metaphor and carrying a history of political critique can be deeply complex. Things have the liberty to get carried away, and to become abstracted and nonsensical.” The artist’s work for the Karachi Biennale masterfully walks this artistic tightrope, as each of the candidates present their hopes for the nation – but to the audience, these caricatures expounding their political spiel from their soapbox all sound interchangeable. The satirical brilliance of this sculptural caricature is that these candidates, their interchangeability and their meaningless rhetoric, seem all too familiar in our disillusionary contemporary political context.

Hopes and Prospects, 2017.

Fiberglass, wood, enamel and animations with audio on a loop

Courtesy the artist