Gordon Cheung studied painting at Central St Martins College of Art and at the Royal College of Art, London from where he graduated in 2001. He is best known for his epic, hallucinogenic landscapes constructed using an array of media including stock page listings spray paint, acrylic and, most recently, inkjet and woodblock printing. Gordon Cheung’s work is in international collections including MoMa, Hirshhorn Museum, Whitworth Museum, ASU Art Museum, The New Art Gallery Walsall, Knoxville Art Museum, Hiscox Collection, Progressive Arts Collection, UBS Collection and the Gottesman Collection. Notable group exhibitions include the John Moores Painting Prize 24, The British Art Show 6 and the Azerbajjan Pavillion at the 56th Venice Biennale.

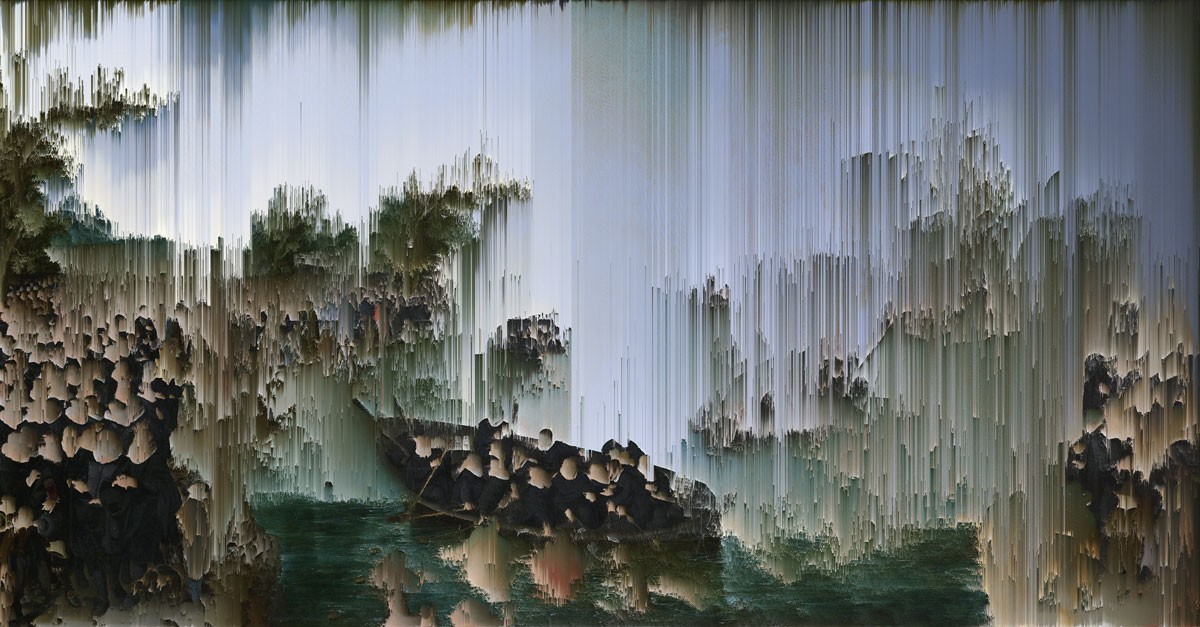

Fishing for Souls is originally a 1614 oil on panel painting by the Dutch Golden Age artist Adriaen van de Venne in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. It was made during what is considered to be the birth of Modern Capitalism with the rise of the East India Trade Company built from militarised trade routes, colonisation and slavery. At the left are the Protestant and at the right the Catholic. Both fish for souls in the wide river dividing them showing an allegory of partition between the Northern and the Southern Netherlands that occurred with the Beeldenstorm, a destructive period of religious imagery. The high resolution photograph of the painting has had an open source sorting algorithm re-organise its pixels into over 4000 images where nothing is erased, destroyed or copied. These are then stitched and looped together in an animation programme. The visual results are a form of deliberate glitching. A glitch is usually a mistake in a technological representation of an image but here it is appreciated for its beauty and how it reveals the multiple dimensions of representation. The digital fracturing of the image simultaneously reveals the technological space of what creates the image, the physicality of the screen and the illusion of image. In these multi-dimensions of reality we are offered a space to meditate and question the narratives of histories. By using this computational code to re-order the pixels the effect results in a mesmerising digital sands of time effect that metaphorically suggests the repetition of histories from the classical to the digital age.

Still from Fishing for Souls (After Adriaen Pietersz. van de Venne, 1614), 2015.

6 min. film loop with 3 hour soundtrack loop

Courtesy Edel Assanti and Alan Cristea Gallery, London